The System that Thirst Built

Water, Rights, Collapse

“And if California slides into the ocean / Like the mystics and statistics say it will / I predict this motel will be standing / Until I pay my bill.”

—Warren Zevon, “Desperadoes Under the Eaves”

I. Water in Name Only

In California, you can hold the rights to a river that no longer reaches the surface. You can own access to an acre-foot of water that hasn’t existed for decades. And if you don’t use that water—if you try to conserve it, store it, or let it stay in the ecosystem—you might lose your right entirely.

That’s not a glitch in the system. That is the system.

California’s water law is built on the doctrine of prior appropriation—a framework imported from the 19th-century American West, where the first person to claim water for “beneficial use” got priority access. The logic was simple: whoever got there first, wins. “First in time, first in right.” It doesn’t matter if you’re upstream or downstream, rural or urban, a town or a corporation. What matters is your claim and the date it was stamped.

This doctrine made a kind of sense in a world of abundant rivers and sparse population. But that world doesn’t exist anymore. Today, there are more legal rights to California’s water than there is water itself. Entire rivers are over-allocated—on paper, they’ve been divided and promised several times over. And yet those rights remain valid, enforceable, and legally protected, even if the water is long gone.

In 2014, during one of the worst drought years on record, a Central Valley farmer told a New York Times reporter he was flooding his fallow fields—not to grow anything, but to avoid losing his senior water rights. “If I don’t use it,” he said, “next time, they’ll say I didn’t need it.” The water disappeared; the right remained.

The system recurses: scarcity is preserved through rights, and overuse is safer than restraint. You can’t just stop using your water allotment, even during drought, because if you do, you risk forfeiting your priority. So farmers flood fields to protect paper claims. Agencies order releases into canals even when reservoirs are nearly empty.

This isn’t just about individual behavior—it’s about how water is governed. The rights are often held and exercised through special water districts, many of which are governed by landowners rather than residents. One of the most significant legal cases in this space—Salyer Land Co. v. Tulare Lake Basin Water Storage District (1973)—enshrined that structure into constitutional logic.

In this case, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of California’s “one acre, one vote” system. The Court reasoned that since water districts primarily manage resources for the benefit of landowners, it was acceptable to weight voting power by land ownership rather than population. This ruling didn’t just reflect how the system worked—it locked it in. It established that water governance could legally operate outside the norms of democratic representation, treating water as a commodity managed by its economic stakeholders, not a shared resource. In doing so, it turned privatized control into constitutional structure.

The result is a system where public survival—clean drinking water, functioning aquifers, livable towns—is subordinate to historic entitlements and agricultural throughput. The system isn’t lagging behind the crisis— the system is producing it.

Tulare Lake itself was once the largest freshwater body west of the Mississippi. By the 20th century, it had been drained, parceled, and converted into agricultural land, its bed carved up into fields and districts. The lake no longer existed—but the rights to its water persisted. In 2023, after record rains hit the Central Valley, Tulare Lake reemerged. It filled the basin like it remembered the shape. Homes flooded. Farms drowned. The water returned. The governance system did not.

You don’t have to go far to see how this logic plays out. Outside Mendota, west of Fresno, there are whole neighborhoods fenced off and abandoned after their wells ran dry. On the gates, signs read AGUA = VIDA. Just down the road, almond orchards stretch for miles, watered by the same aquifer. The homes are gone. The crops are thriving. The water moved according to its paper trail.

Water, in this framework, isn’t a shared resource. It’s a tradable abstraction, separated from geography, ecology, and human need. It moves according to contracts and seniority, not logic or ethics. And because these rights are legally codified as property, they’re extremely difficult to challenge without triggering takings claims or constitutional lawsuits.

This is what a saturated legal system looks like. The paper structure outlives the hydrological one. Rights persist even as the thing they reference disappears. The law isn’t behind the crisis—it’s holding the crisis in place.

And it doesn’t stop there. These rights are enforced through infrastructure—through canals, pumps, tunnels, and reservoirs designed to move water in service of this legal logic. Even when rivers run dry, the system ensures water still moves—on paper, in pipes, and by force. And that’s where we go next.

II. Infrastructure Doesn’t Care Where the Water Is

If the water no longer flows naturally, the system makes sure it flows anyway.

California’s water doesn’t obey rivers anymore. It obeys contracts, seniority, and gravity redirected by energy. The entire state is overlaid with a manmade circulatory system—canals, aqueducts, tunnels, pumps—designed to override nature with a legal map. The infrastructure exists to enforce abstraction: to make the rights real, even when the water isn’t.

The Central Valley Project and the State Water Project together form one of the most elaborate water delivery systems in the world. These projects move water hundreds of miles from the Sierra Nevada snowpack and the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta down to the farms and cities of the south. Along the way, water passes through dozens of engineered choke points—each one governed by seniority, pricing, and contract law. Water isn’t distributed by logic. It’s allocated by lineage.

This isn’t incompetence—it’s precision in service of entitlement. It’s infrastructure doing exactly what it was built to do: move water where it’s been promised, not where it’s needed. In dry years, that promise doesn’t go away. It just gets more expensive.

The California Aqueduct still runs water 444 miles south, even if the rivers feeding it are depleted. State Water Project allocations are issued based on preexisting rights and political leverage, not ecological health. In some years, cities receive only a fraction of their allocations, while large-scale ag contractors buy and bank excess flows. The numbers shift, but the pattern holds: seniority first, everything else after. The infrastructure wasn’t designed for sustainability but for delivery.

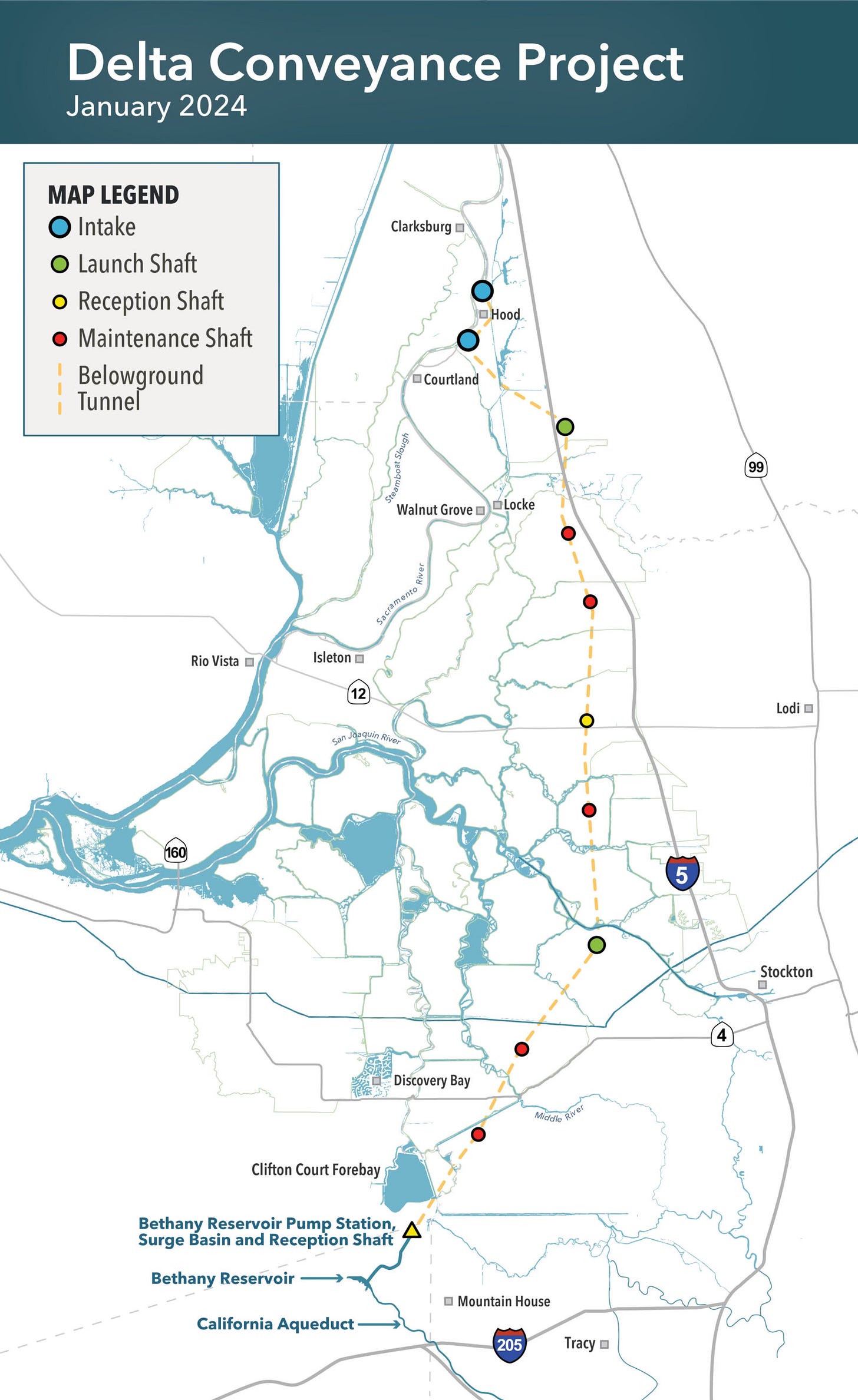

One of the most politically charged pieces of this system is the Delta Conveyance Project, a $16 billion plan to tunnel under the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta to carry water directly to Southern California and large agricultural contractors in Kern County. The communities that would be most affected—like Hood, California—have little political power and were chosen, in part, because of that. Residents of Hood have fought the tunnel project for over a decade, citing threats to their water supply, their farmland, and their community. But their resistance exists in the shadow of a system built to bypass them—literally and figuratively.

This is what infrastructural recursion looks like: every new crisis creates justification for a new fix. Each fix creates a new opportunity for control. And each opportunity for control gets optimized—not for fairness, or resilience, but for volume and extraction.

The water moves south. The land subsides. The aquifers collapse. And the system stays intact.

Take the Kern Water Bank—originally a public groundwater storage facility created to stabilize water supply. In the 1990s, during a drought and a regulatory tangle, control of the water bank was quietly transferred to a private joint powers authority dominated by agribusiness interests. Today, it operates like a strategic reserve for almond and pistachio empires. It stores public water underground, then sells it back when the price is right.

Not corruption, but design: optimized for extraction, not equity. When water becomes scarce, it doesn’t stop being used—it becomes more valuable. The infrastructure doesn’t fix scarcity. It commodifies collapse.

And the only thing that makes that possible is the detachment: between land and river, between users and costs, between water’s origin and its destination. Infrastructure is the interface that maintains that illusion. It keeps the paper rights moving, even when the hydrological system can’t.

In California, the water always moves—even if the river doesn’t.

III. What Doesn’t Flow Gets Buried

In California, when the rivers dry up, the wells go deeper.

That’s the plan, written into the shape of the land: surface water for headlines, groundwater for everything else. For decades, aquifers functioned like a hidden reserve—unregulated, invisible, and assumed to be endless. But they aren’t endless. They’re old, fragile, and we’ve drained them faster than they can recover.

In the San Joaquin Valley, the ground has dropped more than 30 feet in places. Entire canals have warped out of alignment. The California Aqueduct, already strained, has lost up to 20% of its capacity due to land subsidence. And still, we keep drilling.

This isn’t seen as collapse but as adaptation.

“When the water stopped coming,” one Madera County resident told CalMatters, “I knew it was over. I’d already watched two neighbors move out. My well collapsed that summer.”

Some residents still haul water in five-gallon jugs every week. Others install home filtration systems they can’t afford. In towns like Tooleville and East Porterville, water trucks became a semi-permanent fixture—relief efforts that lasted years longer than expected.

Droughts come and go. But for the people left behind, the infrastructure of emergency becomes the infrastructure of daily life.

When surface allocations fall short, almond growers switch on diesel pumps. When new crops demand consistency—no fallowing, no breaks—they pull harder from the ground. When drought comes, it’s not a crisis; it’s a price signal. The system doesn’t pause. It doubles down. And what doesn’t flow gets buried.

The deeper the pump, the cleaner the water—until it isn’t.

In the very basins where we’ve overdrafted most aggressively, we’re also seeing the highest levels of contamination— nitrates from fertilizer, volatile compounds like PCE from dry cleaners, and 1,2,3-TCP—an industrial solvent and pesticide byproduct once smuggled into fumigants by Shell and Dow, now the subject of mass litigation and multi-million-dollar settlements.

These chemicals weren’t illegal. They weren’t rogue. They were optimized.

TCP was never listed on product labels. PCE was considered essential to industrial sanitation. The logic was always the same: if it boosts output, gets results, saves labor—it gets used. No one asked what would happen when it hit the aquifer. By the time it did, it was too late.

Even now, most communities don’t get cleanup. They get bottled water deliveries. They get in-home filtration. They get told to wait for remediation plans that might take decades, to not to let their children drink from the tap. Some sue. Some settle. Some disappear.

Pull up California’s GeoTracker page, type in any city, and watch the colored icons plaster your screen– locations of remediation cases, from underground tanks to military bases to former dry cleaners, the state is steeped in chemicals no one wants to pay to clean up. Cases sit for decades, waiting for responsible parties to be identified, waiting for help from the critically underfunded pool of government aid money, or simply lost and forgotten in the disorganized files of an overworked local government office. Some cases are eligible for closure after years of remediation—but not enough to keep up with the incoming sites.

The next wave is already underway.

PFAS—“forever chemicals” used in firefighting foam, textiles, food packaging—have now been detected in groundwater across the state. The EPA just finalized enforceable drinking water limits for six compounds. But, there are more than 9,000 in circulation.

The lag is baked in.

We don’t regulate chemicals before they cause harm. We wait—for the studies, the data, the lawsuits. And that delay isn’t irrational. It makes sense that public agencies want rigorous science before establishing maximum contaminant levels (MCLs). But the burden of that uncertainty shouldn’t fall on the public. If a compound has a plausible contamination pathway, the financial risk should be frontloaded onto the company—not absorbed by communities while regulators wait for definitive proof.

As it is, only when contamination becomes visible—expensive, political, undeniable—do we draw the line. And by then, the aquifer is already saturated.

This isn’t just pollution. It’s overflow containment. The groundwater basin becomes a pressure sink for everything the system can’t publicly absorb: fertilizer runoff, chemical byproducts, deferred environmental liability. It’s a burial site that keeps the surface clean. A financial buffer. A toxic escrow.

And even then, the market finds use for it.

Contaminated aquifers don’t vanish from the ledger—they get reclassified. They become sites for groundwater banking, speculative infrastructure, mitigation credit schemes. Some become battlegrounds for financial firms seeking payout from lawsuits they never helped prevent. What should be evidence of collapse gets treated like opportunity. The deeper the harm, the more liquid the asset.

This is what a saturated system looks like. The surface stays intact because the damage goes underground. And what goes underground becomes negotiable.

IV. Endogenic Terraforming: Rerouting a System That Works Too Well

California’s water system doesn’t need to be broken to be dangerous. In fact, it works with startling efficiency—just not in the ways we might hope. It rewards water hoarding, incentivizes pollution, and monetizes scarcity, all while draping itself in the legitimacy of law, infrastructure, and economics. But the very logic that sustains this recursive crisis can also be used to disrupt it.

That’s the core of endogenic terraforming: reprogramming the system from within. These interventions don’t reject the structure—they work inside it, rerouting incentives, shifting legal defaults, and introducing new forms of structural drag to extraction. The goal is not to dismantle everything, but to make collapse harder to profit from. Here’s how we might begin.

1. Democratize Water District Governance

Many of California’s water districts still operate under a “one acre, one vote” model upheld by the Supreme Court in Salyer Land Co. v. Tulare Lake Basin Water Storage District (1973). This means landowners—not residents—hold political power over water decisions. It enshrines a kind of structural disenfranchisement: communities affected by water scarcity or contamination have no say in how water is allocated or priced.

Shifting to hybrid governance models that incorporate population-based representation would begin to address this imbalance. Especially in districts responsible for drinking water or large public impacts, democratic input shouldn’t be optional. Legal precedent can be navigated—and in some contexts, challenged outright.

2. Tiered Water Pricing for Export Crops

Crops like almonds, pistachios, and alfalfa use vast amounts of water, but much of their yield is exported. The environmental burden—subsidence, aquifer collapse, contamination—remains in California, while the profits often don’t. A tiered water pricing model could correct this imbalance by charging higher rates for crops bound for export.

This would create a disincentive for water-intensive, high-margin crops that externalize environmental costs. Revenue from these higher rates could be funneled toward rural drinking water systems, recharge projects, or aquifer remediation. It’s not punitive—it’s a reframing of cost.

3. Recharge Credits & Net-Positive Water Mandates

The idea here is simple: if you're going to keep extracting groundwater, you should also be required to help replenish it.

Growers and districts could be mandated to earn “recharge credits” through practices like managed aquifer recharge, stormwater capture, or floodplain restoration. These credits could be traded, pooled, or built cooperatively within water districts. The goal is to tie extraction to restoration structurally—not just as a best practice, but as a condition of continued access.

This isn’t an abstract idea. In Kern County, water districts are already experimenting with recharge banking–storing excess surface water in aquifers for later use– and groundwater accounting systems that allow users to earn credits during wet years for use during dry ones. But without broader mandates or public oversight, these systems remain market-driven and vulnerable to the same optimization logic that caused the problem.

Net-neutral water use isn’t enough in a system that’s already deeply overdrawn. This model would push toward net-positive behavior at scale—turning recharge from a niche conservation effort into a production cost.

4. Pollution Futures for Groundwater

This is more speculative, but could be transformative. Imagine a financial mechanism—modeled loosely on insurance or futures trading—where major polluters are required to purchase risk contracts tied to contamination levels in specific aquifers.

If nitrate levels, for example, exceed a set threshold, payouts are triggered for cleanup or filtration efforts. If levels remain stable, the contracts expire. This structure creates a preemptive signal: a cost to pollution risk before the damage becomes visible or litigable.

It wouldn’t eliminate pollution, but it could change how companies evaluate the long-term risk of their own operations. Think of it as hedging against ecological volatility.

5. Emergency Groundwater Sovereignty

In times of extreme drought, the state should be able to declare certain aquifers under emergency protective status—treating them as strategic reserves, not market commodities. This “sovereignty” would temporarily suspend water banking, freeze speculative withdrawals, and reorient access toward public survival. Like oil in wartime, groundwater should be shielded from hoarding and collapse profiteering when crisis hits.

It wouldn’t be permanent, and it wouldn’t abolish property rights. It would be a targeted failsafe to stop hoarding and collapse profiteering at moments of acute scarcity. If aquifers are strategic reserves, they should be treated as such when crisis hits.

VI. Conclusion: Collapse Isn’t the End of the System—It’s the Signal That It’s Working

Collapse in California doesn’t erupt. It accretes– slowly, recursively, and by design.

Rivers dry up, contracts endure. Land sinks, pumps run. Aquifers collapse, almonds thrive. Filtration units arrive. Optimization persists. Each layer of damage is folded into the next round of optimization.

This isn’t a glitch. It’s a form of governance.

But, we can feel the pressure points– the weight of over-allocation, the brittleness of the infrastructure, the slow saturation of the legal and ecological basin. A recursive system, once saturated, begins to tremble. And when it does, there are choices to be made—not about whether to collapse, but how.

That’s where endogenic terraforming begins– not with revolution, but with rerouting.

We can recode water governance to reflect democratic control, not land-based entitlement. We can tax export crops not just on profit, but on ecological cost. We can demand recharge for extraction. Contaminated aquifers should be treated not as strategic assets, but as systemic failures. And we can build tools—financial, legal, political—that anticipate harm rather than metabolizing it after the fact.

I’m currently working on one such tool: a liability architecture that would force chemical manufacturers to carry financial responsibility for potential groundwater damage before deployment, not decades after the lawsuits begin. If a product like TCP or PCE could plausibly contaminate an aquifer, its makers should bear the cost before the first molecule leaves the lab. The regulatory lag isn’t accidental—it’s structured. And it can be restructured.

Collapse isn’t failure; it’s a price signal. A signal of what’s been chosen, and what’s been protected. The rivers are gone. The groundwater is poisoned. But the rights endure. The contracts hold. The pumps stay on.

The question now isn’t how to save California. It’s who gets to define what survival looks like.